Transparency and the role of the Guardian

9 June, 2010

The Katine Community Partnerships Project (KCPP) is exceptional in its degree of public transparency. The progress of the project, and the lives of people in Katine sub-county, have been extensively documented on the Guardian newspaper’s Katine website since October 2007 when the project started. Much of this has been generated by capable Ugandan journalists resident in Katine, another unusual feature of the project. Intensive coverage is likely to continue on till 2011, if not later. This commitment to transparency was the main reason I became involved in the project, via the Guardian. I had a strong belief in the importance of public transparency as a means of making aid processes more accountable, and in the process, more effective.

AMREF knew the project would receive continuous public exposure when they agreed to the funding support provided by the Guardian and Barclays. They knew they would have much less control over what was said in public than they would normally have, when publicising their own work through the media. It was a courageous decision, and it would be for almost any NGO.

In reality achieving substantial and continuous transparency has not been easy, for either AMREF or its two donors (Guardian and Barclays). The donors have been frustrated at time with the apparent unwillingness of AMREF management to let the project staff speak directly, rather than through layers of approval processes. AMREF has been frustrated by the need to manage what has appeared to be continuing stream of visitors, many more than would normally be accepted by most development projects. The contents of the website, and the public comments made on those comments, have also been a source of friction between donor and grantee. Complicating this picture is the fact that the Guardian in particular does not normally find itself in the role of a donor, with interest at stake in a project they are also trying to report on independently and objectively.

This background has relevance for plans that have and may still be made for the evaluation of the Katine project. I made two visits to the project in 2008 to monitor the early progress of the project, for the Guardian and Barclays. I also provided back up support to a consultant contracted by AMREF to carry out a mid-term review of the project in mid-2009. As stated elsewhere in this blog, my hope was that as the project developed over time, the Guardian would be able to make more use of AMREF’s own evaluations, and rely less on external parties such as myself, contracted by its donors. In retrospect, I think that was an ambitious expectation that has not proved appropriate to the circumstances. There has not been enough trust between donor and grantee for this to happen, and I now doubt the capacity of AMREF to provide an appropriately thorough and rigorous review of the KCPP’s progress.

I have one other concern which I think needs discussion. In the two visits I made, and the mid-term review, the focus was understandably on the project and not on the Katine website. It was however agreed that the impact of visitors (journalists and others) on the project should fall within the ambit of these reviews. With the project now in its third year it is now time to focus on the most innovatory aspect of the whole experience: the Katine website. This is especially important with a project like the KCPP which unfortunately was not a well designed project to begin with. With a project like this, which are all too common, what difference has the Guardian website made? This is a very important question, with potentially wider ramifications for how other international aid projects are managed. There is already some evidence of impact on the project on the website itself, in the various dialogues between the Guardian, AMREF and others. These have related issues like the management of school building construction, drug supplies for the health centres, the scale of investments in livelihoods development and in training activities. My impression is that the Guardian has become a much more engaged/interventionist donor than AMREF has usually had to deal with. And perhaps more than the Guardian itself anticipated. In the aid world being an interventionist donor is not fashionable, but based on my experience it could easily be counter-argued that in fact donors are often too laissez-faire. This view of the Guardian as interventionist prompts a related question: what kinds of impacts (good/bad, anticipated/unanticipated) has the Katine website had? The potential for good and bad is clearly there, especially when you read some of the more venomous comments posted on the website by some readers.

All this involves a significant change of focus, away from AMREF as the responsible agent, to the Guardian as an active party to the development process that also needs to be held accountable, and hopefully, generating some lessons from experience that others can use. Doing so may not be easy. In 2008 I tried unsuccessfully to solicit from the Guardian what their expectations were about their role in the project, with the hope that this would provide some basis for evaluation at some stage. It is worth noting that nowhere, as far as I can see, have the Guardian put their objectives “on the table” on the website for others to see and hold them to account. As an external evaluator perhaps I should have pushed harder to get them to do this early on.

In fact the website is surprisingly non-transparent in dramatic contrast to the exposure given to the KCPP project, and the wider Katine community. Readers posting comments are not required to give their real identity, and the most don’t. It is hard not to think that were verifiable names required the level of discourse would be a good deal more civil and constructive. But according to my inquiries some time ago, the website has to comply with the Guardian wide policy, which is to allow anonymous comments. Others in the media world think it is time for this approach to change (See “Time to clear way the web’s veil of anonymity” in the FT). An evaluation with a focus on the Katine website could make a useful contribution to this debate.

Another non-transparent aspect of the Katine website is the statistics on the performance of the website. These are the equivalent to the detailed performance metrics that donors usually expect from their NGO grantees. Unlike many development projects dealing with social development, useful performance measures for website are relatively easy to identify and to access. These days’ detailed statistics on the performance of almost any website can be accessed via use of services like Google Analytics. However, with the Guardian I have not even been successful in obtaining information about this information .i.e. what kinds of website statistics they have (let alone the statistics themselves). Such information would be directly relevant to an evaluation of the impact of the website. Both in crude terms of identifying what content was read and commented on more versus less, but also where to focus the attention of the evaluation via more detailed inquiries.

There is also another less immediately pragmatic reason. At present there is a pronounced double standard when it comes to expectations about transparency: Good for AMREF, but not necessary for the Guardian. But the golden rule would seem applicable here, as it is often elsewhere: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. With this appeal to principle as well as practicality, I ask the Guardian to focus on what is truly innovatory about the KCPP experience and encourage an external evaluation of the Katine website before the project comes to an end and before the website is archived.

PS1: After the Guardian read this post in draft form they provided the following extra information (paraphrased)

- There will be an “academic review” of the project by Ben Jones (who has previously posted (23) articles on the Katine website), who will visit Katine in September. His work will feed into a public conference to be held in November which will look at the impact of the Guardian and the website on the development process. One of the key questions will be around how honest can one be in the communication of development.

- [RD] This looks like a very positive development

- Re web statistics: According to the Guardian, “it is not straightforward or easy to get figures for specific articles . Media outlets don’t publish their statistics until they are officially audited each month – for the whole site, not for individual sections or articles”

- [RD] I should emphasise that I was asking the Guardian for information about information i.e. what kinds of web statistics they had access to and used, when managing the Katine website. I was not asking for the statistics themselves. Though these would be useful to any evaluator of the website.

- [RD] My impression from the response so far is that there is not much use at all of web statistics in the planning and management of the website, which is surprising. I am open to being corrected.

PS2: Since I drafted this post the new Minister responsible for DFID has issued a public statement on how the new government proposes to increases the transparency of aid programmes funded by DFID. See “Full transparency and new independent watchdog will give UK taxpayers value for money in aid”

Why bother with evaluation?

1 April, 2010

Conflicting views of the likely success of the Katine project

The Katine Community Partnerships Project was scheduled to end in September 2010. In early 2010 AMREF submitted a proposal for a fourth year extension, up to the end of September 2011. By then £3,249,994 will have been spent on Katine, if all goes well. This is equivalent to £108 per person in Katine, assuming a population of 30,000 people.

At the end of the same proposal AMREF make the bold claim that: By the end of a fourth year in Katine, we will aim to have met all our objectives of improved quality of life for the people of Katine.

The same proposal begins with an even more ambitious expectation by “community representatives and local government at the midterm review workshop in Soroti” in September 2009 that “In 2014, Katine will be an active, empowered community taking responsibility for their development with decent health, education, food security and able to sustain it with the local government”

Jo Confino’s final comment in the online debate on the extension proposal is optimistic about the Guardian’s role but more pessimistic about the developmental impact of the KCPP: “So at the end of the year four, Guardian will be able to congratulate itself with fulfilling its media objectives. As for development objectives, I am afraid that I feel rather pessimistic.”

Richard Kavuma’s recent analysis[1] of the Katine sub-county’s capacity to continue to fund KCPP activities post-2011 is also downbeat: “Given the huge discrepancy between the needs of local governments and their capacity to finance those needs, the possibility that Soroti district and Katine sub-county officers will fill the void that will be left by AMREF seems overly optimistic.” He notes that the budget for Katine sub-county in 2009 was UShs 32 million (£42,106), equivalent to about 5% of the annual cost of the KCPP project.

How can anyone tell?

AMREF’s extension proposal has made no budget provision for any evaluation activities in the last year of the project.

There is £3,200 for monitoring and evaluation “Capacity Building”, possibly for elected officials and members in community groups and staff in government offices at sub-country and district level. It is unlikely that these groups will be able to take responsibility for any summary evaluation of the KCPP, given the wider financial constraints on council spending highlighted by Richard Kavuma.

There is also £5,221 budget line for “Documentation”. This may relate to the section of the exit/sustainability plan, where it is stated that: “Analysis of the Katine model, documenting and sharing best practice within Soroti and advocating for its scale up and/or replication at national level by government and bilateral donors in Uganda, especially in the context of the Uganda government policy on Public Private Partnership for Health (PPPH).” (Italics added)

Ideally documentation used for advocacy purposes would be evidence based. But where will that evidence come from? The amounts quoted above stand in pale comparison to the Monitoring and Evaluation budget line for the first year of the project (£17,977), where the biggest cost was the baseline surveys.

Although there is no specific commitment in the extension proposal it is possible that AMREF will continue to provide six-monthly and annual progress reports. By itself this reporting is unlikely to provide sufficient independent and appropriate evidence to resolve the differing claims made above. Resolving them does matter, both to how advocacy work is done within Uganda and how wider lessons are learned from the project by international audiences following the project through the Guardian website

The situation on the Guardian side looks equally unimpressive. There is no budget available for further external evaluation of the project during the last two years of the project (2010-2011). In contrast to the project itself, the Guardian is going through a process of budget cutting, associated with the wider difficulties of the Guardian group[2].

What could be done?

The project has two major assets that could be helpful

Firstly, the KCPP has probably the largest audience of interested bystanders of any single development project that has been seen for a long time. They have been attracted by what must be one of the most comprehensive project websites that has ever been developed. In additional to information provided by AMREF there are also numerous articles both about the details of Katine people’s lives, the political and economic issues affecting them and how these relate to the wider Ugandan context. There is a large amount of information available, and large audience of potentially interested users of that information.

Secondly, the Guardian has its own resident independent Ugandan journalists who have been the produced much of the information on the website. Hopefully they will continue to cover the project until it comes to an end. During this remaining time it would be possible for their work to take on more of an evaluation function. This could be done through means of inquiry they are already familiar with: a series of in-depth interviews with a wide variety of people, both at the end of the project, and then with the same people at least one year later. Ideally the people interviewed would be from all four of these groups: (a) Households (men, women, children), (b) Community groups (e.g VHTs, PTAs, WSCs,Farmers Groups, VSLAs etc), (c) Staff managing health and education services in Katine, (d) District and sub-county officials.

While it is important to know what impact the project activities have had by the end of the project, the more important question is the sustainability of what has been achieved. With this concern in mind the journalists could focus on obtaining (testable) predictions from the people they interview about what the situation in Katine will be like in a year’s time, after the project has finished. These predictions could be about: (a) the state of schools and health services, (b) the functioning of community groups, (c) the welfare of households, Ideally these predictions would specific rather than general, and include some explanations. For example, about the number of water sources that will still functioning, the number of functioning VSLAs, the number of women coming for immunisation and ANC at the health centres, etc. While many people may not be able to predict actual numbers it is likely they could be willing to predict the direction of change, i.e. increase, decrease or no change. In a year’s time the Guardian could fund a return visit by the journalists to find out what has actually happened, and why. A lot could be learned from such an exercise.

Some questions about the current impact of the project activities could also be explored. This could be done through comparison questions of what has been provided, and with what has not been provided. For example, individuals could be asked:

- “If you were given UShs 300,000 at the beginning of the AMREF project in 2008, how would you have used it?

- What about the other members of your household, if they were also given the same amount?

- “From what you know about what AMREF has done here since 2008 would you have preferred that AMREF kept that money and used it for community development activities here in Katine?

If the Guardian was able to follow this journalist-led-evaluation path they may be able to test a hypothesis of my own: that in some circumstances it may be more cost-effective for donors to contract independent journalists than to hire external evaluators. So far the Guardian Ugandan journalists have produced much more informative reporting on the project than I have produced as the external evaluator. Their reports have probably been much more widely read and have provoked more responses than my own. And they have cost less.

Crowdsourcing

This was an idea of interest to the Guardian at the beginning of the project. Via the Katine website, it has been applied to problems relating to material supplies (e.g. solar panels to provide electricity where the mains system is not working) and also to questions of project design (with less clear success).

Given the volume of data collected on the Katine project and community, and the continued availability of the Guardian journalists on location, it would seem to make sense to try to crowd source the names of some potentially interested parties who could make best use of it all, and in the process synthesise some final conclusions. I am thinking of research and teaching institutions as the most likely candidates.

[1] http://www.guardian.co.uk/katine/2009/dec/15/local-government-funding

[2] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/mediatechnologyandtelecoms/6545303/Guardian-News-and-Media-to-make-more-than-100-new-job-cuts.html

Coordinating aid to Katine

9 October, 2009

Richard Kavuma has writen an interesting article about the role of insecticide treated bednets in preventing malaria, especially amongst young children in Katine (See Net gains in preventing malaria). His article notes that while bednets have reduced malaria there are other important prevention measures that are not being addressed, most notably ensuring a continually available stock of anti-malaria drugs in the local clinics.

I was very interested to read that there was another agency that was providing bednets in Katine, and in other areas of Soroti District. In fact “Since August 2007, … PSI Malaria Control, which supports governments with malaria prevention programmes, has given out 89,660 nets to households in the district’s 17 sub-counties – including Katine.” This compares to the 5,478 bednets given out by AMREF in Katine.

Amongst international aid agencies, especially bilateral (government) and multilateral (inter-govermental) there has been a strong movement over the last decade towards greater coordination and harmonisation of their aid efforts. These intentions were documented in the 2005 Parish Declaration, and have been systematically monitored since then.

Richard’s story raises questions in my kind, and perhaps others, about the reasons for AMREF being involved in bednet distribution, when there another agency present in the district doing the same thing, but on a much larger scale, and possibly with more specialist knowledge in this area. Did PSI start their distributions after those made by AMREF? Could AMREF’s resources (funding and staff) now be better directed elsewhere? Or are there good reasons for AMREF to continue providing this additional channel for bednet distribution?

The reference in Richard’s story to families buying ordinary (untreated) bednets raises a related set of issues. What has happened to the private sector suppliers of bednets to Katine (and Soroti as a whole), since the distributions of free treated bednets by PSI Malaria Control and AMREF? Have their sales collapsed, or have they expanded? (and does AMREF know what is happening here?) It seems highly likely that the only way treated bednets will continue to be made available to families in Katine after the current project comes to an end will be through the private sector suppliers, if theyare still in this business. Is AMREF thinking in these terms?

Mobile phones, the internet and innovation in Katine

1 October, 2009

One of the often claimed advantages of providing aid through NGOs is their ability to be more innovative, especially when compared to government structures. In practice innovations by NGOs are not as common as one might expect, at least in my experience.

One of the more interesting features of the KCPP is the setting up of a “community media centre” which has four computers connected to the internet. This is in a large room in the same building as the AMREF office, which is about a hundred metres from the Katine sub-county local government offices, and just off the main road that runs north-south through the centre of the county. In the last progress report provided by AMREF, earlier this year, it was reported that

“More than 100 community members have received basic training in computer skills so they can write simple stories. There is a committee who oversee the resource centre from the community. 30 people were specifically selected and trained as Trainer of Trainers. About 40 school children also received similar training from both primary and secondary schools. Over 25 community members visit the media centre daily to seek knowledge and learn. Some read and contribute to blogs on the project website. A media centre committee has been formed by the community to be part of its running”

AMREF’s Mid-Term Review subsequently reported in August that:

Five centre users were interviewed together with Joseph Malinga the Community Media Facilitator. More than 100 people have been trained in basic computer skills. All five of the users have posted blogs on the Guardian website, they are know as ‘Katine Informer’. All five use email, four email outside Katine and two of those email outside Uganda. The users considered that the service would be sustainable; they saw the possibility of an internet café provider from Soroti running the centre although they were fearful of the cost as twenty minutes of internet time in Soroti costs the equivalent of a meal. Two on-line chat sessions have been held, linking school children in Uganda and the UK. Some equity issues exist; people with poor, or no, English are disadvantaged.

What is the objective being pursued, and how will we know when it is being achieved? One seems to be to provide opportunities for Katine residents (other than AMREF staff) to participate in the discussions taking place on the Guardian website. This has happened, on a modest scale. The other may be to provide internet café facilities which are more accessible, in terms of location and cost. This is happening, though as noted above, there are big questions about sustainability that need to be addressed. In the short term it will be useful if AMREF could provide some detailed statistics on usage of the internet facility since it started, including total number of users (broken down by gender at least) and some form of frequency distribution showing numbers of visitors x number of visits by them. Are a small number of people using the facility frequently and the rest only once or twice, or is use more evenly spread?

Is this all there is? Or could more be done with this facility? AMREF reported on the media centre under the heading of “Empowering communities with information, knowledge and exchange of ideas”. If that is the wider objective, then how could it be achieved?

The Economist of 26th September has an interesting article on telecoms in emerging markets, that if read could prompt some more imaginative thinking by AMREF about the possibilites. Uganda is mentioned a number of times, as a place where there is rapidly expanding mobile phone coverage, and where there are some interesting innovations in the types of services being provided via mobile phones. Some of these are being supported by Google, the Grameen Foundation and the mobile phone networks themselves. They include provision of agricultural information via text messages, as well as the better known money transfer services.

Despite the poverty of many households in Katine, mobile phones are not a rarity. There are enough around to make it worthwhile for at least one person in Katine’s Tuesday market to earn income by charging people’s mobile phones using a truck battery (See Guardian article on this). On my first visit to Katine I was surprised to find that mobile phone reception in the sub-county is better than in the part of outer Melbourne where my mother lives. Katine’s open and flat landscape helps.

AMREF’s baseline survey of Katine, carried out in late 2007, did not ask about mobile phone use, nor did the more recent survey contracted by CARE in early 2009. The focus of both of those surveys , like many development project baseline surveys, was on deprivation and constraint, rather than opportunities. Perhaps it is now time to investigate the opportunities people see around them, and work on how access to those opportunities could be improved. Time could be spent finding out more about the access to mobile phones (owned and borrowed) and the purposes they are used for. The new road is also likely to be seen as an opportunity by many people in Katine, and not just a risk (e.g. more vehicle accidents and more HIV cases).

The Economist article highlights a number of possibilities that could be explored in Katine. One is the role of intermediaries. In Bangladesh this first took the form of a woman (a Grameen group member) in each village selling mobile phone use (for incoming and outgoing calls) to others in the same village on a call by call basis, while buying the phone from Grameen on an instalment basis. Would this be possible in Katine? Is it already happening on an informal basis? More recently Grameen is looking at the possible role of “information intermediaries”, who can help others get access to particular mobile phone based information services. In Katine that role could be expanded to helping others access useful information via the internet, without having to use the Community Media Centre computers themselves (remembering that a high percentage of Katine residents are not literate). These “infomediaries” might the ones would could afford to pay for internet access, and be willing to do so.

More information is needed, about the use of mobile phones and the use of the internet in Katine. With the current users of the internet in the Community Media Centre what services are they using? Email, text chat or skype for communications? Visiting social networking sites or using Google for information searches? For information about Uganda matters or about the rest of the world? Looking forward it would then be useful to try to idnetify Uganda -specific information is available on the internet, which might be of most interest to Katine residents. Provided by the government and others.

Re the use of mobile phones I suspect there are many innovatory uses already being explored by people in Katine, but not yet widely appreciated by aid agencies and donors. For example, to what extent are government officials already using mobile phones to submit verbal reports, or at least texted data on key indicators? How often are meetings being convened through networks of phone calls? Are any farmers receiving commodity price information through their telephone contacts? Further afield is the whole area of money transfer. Are households receiving money transfers from Kampala via mobile phone, and at what cost?

According to the Economist a recent study found that “adding an extra 10 mobile phones per 100 people in a typical developing country boost growth in GDP by 0.8 percentage points” Would connecting up a local population of mobile phone users with skilled internet users lift this figure further? Or should any investments that can be made focus on exploiting the uses of the most widely used technology, i.e. mobile phones rather than the internet?

Negotiated agreements on AMREF-assisted developments

23 September, 2009

On Tuesday 22nd September Joseph Malinga wrote an article titled

Building work begins on Katine produce store: Katine farmers dig the foundations of a produce store that should help to improve livelihoods in the sub-county

I posted a Comment as follows:

Negotiated agreements on AMREF-assisted developments

It is good to see the issue of uncertain and conflicting expectations being dealt with in this article about a specific development activity assisted by AMREF: the building of a grain store for use by farmers groups in Katine. The need for written agreements about expectations has been raised by the farmers and AMREF has responded to (or has anticipated) this need. The only question in my mind, and perhaps others, was whether this agreement should have been negotiated and signed, before the commencement of the work on the store. On the other hand, a positive feature of this agreement is the willingness of government to make its contribution, along with that of the farmers groups (though this has its risks as well). And the agreement does not seem to be one sided in its expectations. Such agreements could go further than specifying the inputs each will provide, and management arrangements once completed. Reference could also be made to the objectives of this investment, to help forestall any future misuse of the store, e.g. the private use of the store by one of the farmers group members, or someone else completely. How ever the agreement does develop, it would be good if AMREF could share this example agreement via the Guardian website.

In my August 2009 comments on the future of the KCPP I had suggested that Associated with this clarification of expectations, agreements need to be developed that will spell out not only what AMREF will provide, but also what communities will provide, AND what the government will provide. Multiple agreements may be needed, perhaps component by component. One generic agreement will probably not work, because responsibilities will become too generalised and fuzzy. My proposal did not go far enough, agreements about individual developments, such as the grain store, are better still. They are smaller in ambit, and more manageable.

“When the community owns the project Giving the community a say in how their schools are built seems to be the most sensible option, says Joseph Malinga”

21 September, 2009

This is the headline of a recent post on the Guardian Katine website, by Joseph Malinga, a Guardian journalist based in Katine.

I posted the following reply…

Could Joseph Malinga do a follow-up to this story explaining what the government (local and/or central) is doing to support community initiatives like this one? Joseph’s story describes what the community is contributing and what AMREF is providing but there does not seem to be any matching contribution from the government. The government appointed head teacher was there already. The only government contribution so far seem to be doubt, about whether the quality of the school building will be adequate. Yet government is supposed to be one of the partners in the Katine Partnership Project, and advocacy is reported to be an important part of AMREF’s development strategy. What contributions or commitments have AMREF secured from government, in return for the work AMREF is doing with these two community schools? For example, the provision of more government paid teachers. At present the community is paying the teachers salaries.

This is an issue I have raised in my review of the Mid-Term Review, at https://evaluatingkatine.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/a-process-review-of-the-katine-mtr.pdf

“The Worst Question to Ask About Charity”

21 September, 2009

In the recent Mid-Term Review (MTR) of the KCCP some local officials questioned the amounts being spent by AMREF on management, and the amounts remaining for what they thought was most important, the construction of infrastructure, like clinics and schools in the Katine. They wanted more for infrastructure and less on management.

In her report, the MTR consultant said “ Just how much money is available is a figure that can be misrepresented but the entire sum when broken into management, transport and staff costs leaves a reasonable – but not excessive – amount for activities and work on the ground. The figure is at least 70 per cent of the total budget and this is regarded as an acceptable amount in development projects worldwide.”

In the minutes of a subsequent meeting between AMREF and its donors (Guardian and Barclays) it was reported that the Guardian “asked for costs to be streamlined however [AMREF noted that] management support costs need to be factored in since this came up as an important resource to consider in the review. The MTR recommended a 70%/30% split as common with other projects”

I have real disquite about this position for several reasons, which I will explain. The first reason is it is actually not so easy to calculate this percentage in a standardised way that is applicable across all organisations and understood by all donors. The 70/30 split is probably a common view because everyone in the aid agency world has formed the view that this is what is acceptable to everyone. In other words, it is a herd judgement. I doubt that it is a percentage that has been found through any systematic assessment of aid agency costs.

My second reason is that this crude measure of overhead costs is based on a false assumption of how aid agencies work, a view which is captured by the simplistic but appealing notion that what matters is “whether the money gets there”. In practice in most aid programs very little money or goods actually reach the hands of poor households, because that is the way projects are designed. In Katine more than 50% of the activities in the workplan are training activities, directed at different members of the community and local government. The money spent here goes on staff salaries, and allowances for other trainers, which are spent mainly in the towns. Building costs are another important part of the project. Until recently, most of the money spent on infrastructure was spent on contractors hired from Kampala. Only in the livelihoods component is there much in the way of actual transfer of project resources directly to poor households, in the form of seed supplies. But in parallel to these activities is the UWESO-assisted savings and loan project, where instead of giving people things, the aim is to help people save and make best us of the money they already have. Only in humanitarian emergencies is there any deliberate and substantial real transfer of assets to poor households. [PS: But a small number of aid agencies have been experimenting with cash transfers to poor hoursholds, in non-emergency contexts]

My third reason is that the percentage spent on management costs versus delivery of services is an efficiency measure. Notionally, the smaller the proportion spent on management the better. But this completely ignores the issue of how effective the services are that are delivered on the ground. Low overheads will not redeem poor quality services. High overheads may contribute to better services. What matters here is cost effectiveness – what can be achieved for a given unit of cost. And cost here include not just immediate costs like building materials, but also the associated management costs, and (proportionally) the costs of the managers of the managers, etc.

In a recent posting by Dan Pallota on his blog “Free the Non-Profits” he quotes some findings from America which may also apply in the UK:

In 2002 the Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance commissioned a study that asked respondents what information they wanted when considering donating to a charity. Seventy-nine percent wanted to know what percentage of their donation went to charitable programs. Remarkably, only 6% wanted to know if the donation would make a difference. How can that be, you ask? Well, the media, the watchdogs, and the sector itself have done an amazing job of training the public to think that the two things are the same, i.e., that if a charity has low overhead, it must be making a difference. Major studies on the relationship between organizational strength and impact find otherwise.

My advice to AMREF, the Guardian and Barclays is to forget about the 70%/30% ratio, however it is constructed. I agree with Dan Pollota when he says the worst question to ask about charity is, “What percentage of my donation goes to the cause?”, also known as the admin:program ratio, the “efficiency” measure, or the overhead ratio. Whatever you call it, it’s hopelessly flawed, widely abused, utterly useless, a pathetic substitute for meaningful information about a nonprofit’s work, inept at exposing fraud, and a danger to human life”

Okay, then how do we best address the concerns expressed by local authorities, during the Mid-Term Review. In my process review of the MTR I made the following suggestion:

The Guardian and Barclays Bank could take a further step, and request that each six monthly narrative progress report on the KCPP include seperate sections on the activities of the AMREF London and Kampala offices and the costs they have incurred in carrying out these activities. If this step is taken, these narrative reports should then be routinely shared with the Steering Committee and Management Committee, as well as being made publicly available via the Guardian website as at present.

These additional sections would detail not only the costs incurred by different sections of AMREF (London, Nairobi, Kampala), but also what they were able to do with that money i.e. some description of their effectiveness.

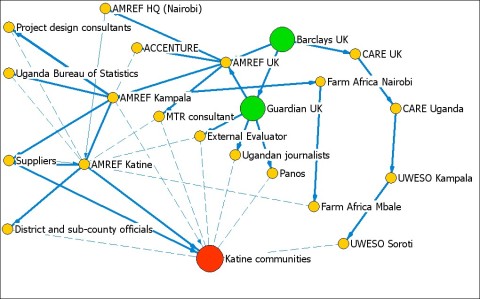

There is an important larger lesson here. Aid projects like the KCPP involve long and complex supply chains, bringing funds and technical expertise to communities of concern, from distant locations. In the private sector intense effort is often invested into making every part of supply changes work as quickly and efficiently as possible. But in the world of development aid often the focus is almost wholly on the final link in the chain, the organisations delivering assistance at the grassroots level (e.g. the AMREF office in Katine). Very little attention is given to the more expensive[1] parts of the supply chain lined up behind them. The Guardian needs to turn its journalistic attention towards the issue of supply chain costs in international aid delivery. The diagram below shows just how complex these supply chains can be, even in a modest project like the KCPP

Thick blue lines = financial transfers. Broken blue lines = information transfers (not including most of those between yellow nodes (intermediaries between donors and recipients))

For further reading see Dan Pollota’s posts on

The Worst Question to Ask About Charity 9:44 AM Tuesday June 16, 2009

“Efficiency” Measures Miss the Point 3:56 PM Monday June 22, 2009

Beware of Highly “Efficient” Charities 10:44 AM Monday June 29, 2009

Efficiency Measures Discriminate Against Lesser-Known Causes 10:40 AM Wednesday July 8, 2009

Efficiency Measures Short-Change Individual Action 2:20 PM Monday July 13, 2009

[1] In terms of the costs of staff time and transport costs involved

Reviewing Katine: What’s happening with governance?

30 June, 2009

In her recent posting on this topic, Madeleine Bunting said “I’ve listened to Joshua Kyallo, Amref Uganda‘s director, explain how villagers can be empowered to demand better services from the government at district level. But there are plenty of questions in my mind as to how effective this will be in improving the operation of state services in Katine….The district budgets for health and education, for roads and water are desperately inadequate. It is not just the lack of demand for services that causes the state to be so ineffectual at village level here. I find the “rights-based” approach, based on developing in villagers a sense of entitlement to basic health and education, hard to understand”

Before asking whether the rights based approach is affective we need to ask if AMREF is in fact pursuing a rights based approach? As of August 2008 I could find no evidence of this on the ground, though the Country Director did affirm that AMREF supported a rights based approach. There are other interpretations of what empowerment is all about. The simplest and easiest to realise, is individual empowerment through the provision of practically useful information, for example, how to reduce the incidence of diarrhoea by maintaining clean water sources. This sort of empowerment was being addressed by the AMREF project in 2008. But it does not address wider issues such as the willingness and capacity of government to provide basic health services. Perhaps the project strategy has turned more in this direction since August 2008. The Mid-Term Review needs to look at this.

In the same article Madeleine Bunting also noted “Several of the Amref staff spoke of how they had struggled with huge expectations of the project from Katine villagers. Is that the Guardian’s fault, I asked, with its headlines promising “transformation”? Perhaps partly, they agreed…I wondered how actively Amref has managed expectations and how widely it had communicated with villagers across this very scattered sub-county about what the project was going to do and what it was not going to do”

Expectations are usually about objectives and how they should be reached. If they are diverse this suggests that communication and negotiation about project objectives may not have been as effective as they should have been. Madeleine Bunting’s article raises two possible causes: (a) insufficient communication with local communities by AMREF, and (b) the influence of the Guardian’s frequent visits to Katine communities. It could of course be both.

Another possibility is lack of clarity within AMREF itself, about what the project was trying to achieve. This was a concern I expressed in the first paragraph of my first visit report in January 2008. “The final objectives of the project may need clarification and agreement, by AMREF, its donors and local stakeholders. This agreement should be evident in a smaller set of indicators that show changes in people’s lives, reflect the impact of all five project components, and which can be easily be monitored by community groups.” At that stage the monitoring and evaluation framework had 35 indicators about expected changes in the lives of individuals and households and 60 indicators about the expected changes in the functioning of community groups and organisations. These are large numbers by the standards of most development projects. Later in 2008 the project staff in Katine made some efforts to prioritise these and focus on some key expected outcomes. One of the questions for the MTR should be looking at this year is the clarity of objectives within each of the components – within AMREF in the first instance, then amongst the wider group of stakeholders.

Reviewing Katine: What’s happening in livelihoods?

27 June, 2009

In her article on this topic, Madeleine Bunting commented “The livelihoods component of the Katine project has caused ongoing concern. Many times we have reported, and observers have commented, that not enough of the budget has been devoted to improving livelihoods. The vexed question over whether we should be giving what the villagers have repeatedly said they wanted – cattle – has repeatedly been raised.

Some of this disquiet seems to have been taken on by Amref and Farm-Africa because some interesting shifts in policy seem to have taken place. There is more emphasis on giving inputs – this is described as “hardware” in development lingo – such as seeds, tools, wheelbarrows and watering cans. The balance between hardware and “software”, or training, has been reversed in the livelihoods component so that more is being spent on the former.”

Later in the article Madeline rightly asks, in relation to the upcoming Mid-Term Review, “Can we have some explanation of why the approach on livelihoods shifted?” The reasons matter. A subsequent comment from Farm Africa, who provide technical support to the Livelihoods teams, provided some clarification. They reported that “The software to hardware shift was in response to political pressure rather than internal reflection and learning. Politicians, especially at the sub-county level, were comparing KCPP with Government programmes that are hardware heavy, for instance the Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF). The livelihoods component in particular was also being compared to the other components; Water, that sinks and rehabilitates boreholes; Health and Education, that build clinics and classrooms respectively, and being told to put more into hardware.”

While AMREF has obliged by providing more “hardware” such as seeds and tools, Farm Africa “are more convinced than ever that the approach of giving more seeds than trainings is not prudent. A significant number of the seedlings in the nursery had failed, mainly due to poor management, perhaps as a result of a lack of follow up training. This follow up training for the seedlings was not feasible due to the amount of the budget that was diverted to hardware. The backbone of our approach has always been to increase production by introducing new technologies and techniques rather than handing out seeds.”

This development is worrying for a number of reasons. Many development NGOs, including probably Farm Africa and AMREF, would argue that advocacy is an important part of their work, and that they have competence in this area. If so, why has Farm Africa caved in on an issue it believes in? Is it because they were unable to provide solid evidence from their projects elsewhere that training does make a difference? Or, was it simply the case that local authorities were impervious to the evidence that was presented, because they were trying to meet their constituents’ needs, regardless of their wisdom? Both prospects should cause some re-thinking. The same questions also apply to AMREF, who have been party to this change in direction. In the last (“Conclusions”) page of their 2007-2017 corporate strategy it is stated that “As we gather knowledge and evidence in our programme work and research, we will develop advocacy initiatives to influence policy makers to promote identified best practices.”

The issue of actual evidence is important. It is not self-evident that training will provide more sustainable development than material aid. Part of the “theory-of-change” behind the provision of training is the assumption that information about good agricultural practices (for example) will be passed on from one farmer to the next. Examples have been identified where this has happened. But comments by others (“Dr Jazz”) underneath Madeleine Bunting’s article also highlight the fact that in some cases neighbours not only do not cooperate this way, but they actively sabotage each others efforts. Another commentator (“Ugandalife”) noted that that in their experience ” information is not generally shared easily. Information is considered an asset and therefore worth money. We have encountered this several times and it is hard to change this attitude.”

The idea that good practices will be imitated and reproduced by others is widespread amongst development projects, in just about all sectors e.g health, education, water and sanitation, livelihoods, etc. But just as common is the widespread failure by development agencies to invest any time and effort into systematically monitoring when and where (i.e. under what conditions) adoption by others actually takes place. This is worrying, because it suggests that many development agencies are isolated from important important strands of thinking that they could learn from. For example, the considerable body of literature that now exists on the “diffusion of innovation” Ironically, much of the early research in this field was done in relation to the adoption of agricultural research findings.

One of the implications of the concerns outlined above are that the MTR team should pay attention to: (a) where assumptions are being made about good practices being adopted by others, (b) what efforts are being put into monitoring how, when and where this is happening.

….

A second set of questions was asked at the end of Madeleine Bunting’s article: “Has some thought been given as to how to mitigate the tension over the fact that only a few people are benefiting from the free seeds and tools?

How significant are those tensions – are some people benefiting much more from this project than others? Could the project end up causing more disagreement and community fragmentation at a local level?”

Good question, worth trying to answer, under the ambit of equity concerns. If there are tensions there are two possible solutions, but only one of these has been discussed much so far. That is the try to extend coverage to all households. That is an expensive task and apparently beyond the current budget of the project. The other is targeting of households most in need. There has been little explicit discussion of this option, as far as I can see.

Farm Africa’s response to the Madeleine Bunting’s second set of questions was that “As far as we know, there is no significant tension within the community as a result of the intervention. One of the reasons why there is no tension, is because the beneficiaries we are working with were not hand picked by the organisations, but rather selected in a participatory and open process involving different stakeholders through an agreed criteria.” The MTR team needs to find out more about this process, including the agreed criteria. And the results of the selection process. For example, it would be interesting to know what proportion of beneficiaries are from illiterate families (about 16% in the population at large) and from families with high dependency ratios (few able-bodied workers and/or many dependents). Or from the 15% of families that reported only eating one meal a day, in the January 2008 baseline survey.

Opening up the Mid-Term Review process

24 June, 2009

Madeleine Bunting’s first of five articles on the components of the Katine project is very timely, and the intention of the series is spot on. They relate to the forthcoming review of the progress of the Katine project via a process known as a Mid-Term Review (MTR). Her hope is that her pieces “… will provide a useful rough draft with a few pointers for the professionals [i.e. the MTR team] who will follow, which is why I’ve listed my questions – please add any that you have which you would like the mid-term review and our independent evaluators to consider”

The MTR process

The MTR team will begin their work from next Monday 29th June, and are expected to produce a report by late July. This review is probably the most important review process during the whole of the life of the Katine project, more important even than the end-of-project evaluation. This is because the results could influence decisions taken over the next year, about (a) what the project should try to do in the remaining time left and (b) what should happen after the project officially ends in late 2010.

Part of the planning process for a mid-term review is the development of Terms of Reference (ToR) which will guide the work of the MTR team. They normally spell out the purpose of the review, the scope of activities to be reviewed and nature of the final products expected. Along with other information on the background of the project, and expectations about how the review will be undertaken. Normally ToRs are subject of negotiations between the stakeholders involved, including the donors (e.g. Guardian and Barclays), the implementing agency (e.g. AMREF) and local partners (e.g. government bodies and community groups in Katine). This process is already underway and will continue up to early next week when the MTR team visits Kampala and Soroti. As with the first two visits to the Katine project by myself (the external evaluator), the ToRs will be made public via the Guardian website. What is different this time is the opening up of the ToRs consultation process via the Guardian website, and Madeleine Bunting’s articles this week in particular.

The points raised by Madeleine’s posting on the health component

At the beginning of my work on the Katine project I proposed that we should use seven criteria for evaluating the project. Five of these are OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) criteria: relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability. Two others I suggested to be included are: equity (fairness of process and outcome) and transparency.

One of the challenges for the MTR team is which of these criteria to apply to which project component, because applying all would mean a much more time consuming MTR process, which may not be affordable (in the wide sense of the word).

Re the distribution of anti-malaria bednets Madeleine Bunting asked “Has there been any coordination to avoid overlaps between AMREF and other donors on this issue?“, that is the distribution of bednets by different agencies to the same community. This question is concerned with efficiency. We could also ask about equity, who is actually using these within the receiving households…children or adults, mothers or fathers. The intention was, I think, that children should be using them, because they have less resistance to malaria. We could also ask about sustainability: Where will households get replacement nets in the future, after the project ends? My feeling is that the equity and sustainability questions are more important here than the question of efficiency.

A number of Madeleine’s questions relate to the criteria of relevance. Are the existing project interventions the most appropriate means of addressing the pressing health problems? Would some form of ambulance service help ensure women with birth complications were able to get to a doctor in time for a caesarian birth? Is “empowering” villagers in Katine with health information enough, when government services are so inadequate in the delivery of drugs and medical staff? Would some form of community health insurance be a useful means of topping up drug supplies or health centre staff pay.

Relevant – compared to what?

In order to answer these questions the MTR team will need to try to understand the project design – what were the objectives and what was the plan for achieving them. It could be unfair to assess a project in relation to an objective it never prioritised in the first place. Part of this process involves a reading the initial project documents and any official revisions to the project design thereafter.

The Katine project did develop a “Conceptual Framework” at the beginning of the project in September 2007, which spelled out what some people call a “Results Chain, showing how AMREF activities would contribute to the achievement of improvements in health, education, water, sanitation, health, livelihoods and governance.

In the health component the expected outcome was “Increased community awareness of, access to and utilisation of health services in community and health facilities” This presumably covers both the services provided by the Village Health Teams, and the two tiers of government health centres with Katine (HC2 and HC4). This is quite ambitious given that there are only two AMREF staff working on the health component over a three year period. Therefore some prioritisation of the kinds of people who should be using health services more than before, and the kinds of health services they should ideally be using more than before, might be expected. Hopefully these prioritisations would be aligned of those with local government planning bodies and the Katine community (i.e. they would be seen as relevant). These issues are aspects of the health component that the MTR team could be looking at.